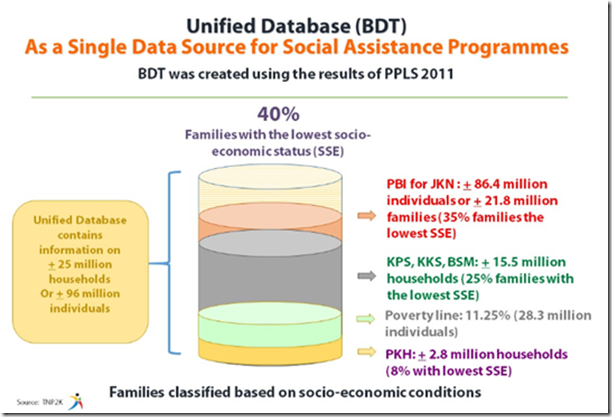

There has been a remarkable achievement in Indonesia over 2014, as the national poverty level reduced to 11.25% from 13.33% in 2010 and the Unified Database (BDT) launched as a single source for targeting social assistance programs. TNP2K is the Indonesian National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction (TNP2K) and co-ordinates this work, as part of their duties relating to poverty reduction.

I recently caught up with Michael Joyce, Mobile Money Policy Advisor at TNP2K as part of our research work for our soon to be published viewport “Digital Money in Indonesia 2015”. In this blog I am pleased to share highlights from our discussions, to reflect on important regulatory changes from 2014 and consider how they are likely to impact the adoption of digital money service in Indonesia.

Michael, could you please give us an introduction to TNP2K and your role there?

TNP2K is the Indonesian Government initiative to improve delivery of poverty related programs. It operates to promote financial inclusion with the support of Australian Government through Australian Aid (DFAT) and USAID. It maintains a key database that targets poverty reduction through work promoting electronic payments to improve financial inclusion for poor households.

I’ve been here for two and a half years, and work on regulatory and implementation advice for different parts of the Indonesian Government, to try to improve the financial inclusion benefits.

Could you provide some background on the Indonesian context and developments over 2014?

In terms of a review of 2014, there has been a lot happening with OJK work, payments for some subsidy relief programs and in summary, a significant drive towards e-payments.

Indonesia is an interesting market, with officially only 20% financially included, though anecdotal evidence points to around 50% included. There is a strong savings culture and willingness to save. However the tools and price points are not geared towards reaching the large informal sector. Until 2014, digital finance initiatives were slowed down by regulations.

Although E-money licenses were issued there were restrictions on how these could be used in terms of cash-out services at agents. So banks had not been able to use agents up to now. There is a highly fragmented market, with over 17 e-money licenses, but none gaining traction or able to offer a full suite of services.

We started to see a change in 2013, with pilots geared towards reaching the unbanked. In 2014 the results of the pilots were enacted through a law on electronic money and the concept of LKD or “Digital Financial Services”.

Can you tell me why a new regulator was needed and how this has panned out?

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK) was created as a new Financial Services Authority in December 2013, and this is similar to the UK and Australia model. This separates monetary policy from prudential regulation. Prior to this, Bank Indonesia (BI) was the single authority that combined roles of a central bank (such as monetary and interest rates) with responsibilities with regards to Payments.

OJK is now the prudential authority. It has proved to be a good thing, as the role has expanded a lot. While Bank Indonesia had more of a bank-related focus, OJK is now better focused on additional areas such as the non-bank financial industry. OJK looks at microfinance (MFI), rural requirements and non-bank providers and this opened up a new potential to bring lots of areas under one roof.

It always takes time for dust to settle, and establishment of the new regulator and transition to them did slow things down in terms of financial inclusion – for instance the pilots had to be terminated in terms of better transition to OJK.

How have the new regulations changed things?

The e-money regulations issued by BI tend to favour the four big banks against smaller banks and telcos. Larger banks can offer a wider range of services through agents. However smaller banks and telcos are restricted to using formal entities as their agents. This proved to be a real restriction as it limits small banks and telcos to formal retail chains, co-operatives and pawn shops, but excludes the mom-and-pop stores that are more commonly found in Indonesia.

The new regulations recently released by OJK provide for a much broader set of services and allow a variety of banks to offer services through agents. OJK was able to obtain and act on industry feedback since the first draft in August, and the final release addressed concerns from a range of stakeholders.

This will let a variety of banks offer effective basic banking account services. There can be a nil minimum balance and they can charge transaction fees lower than normal. At the same time KYC provisions are strong and it properly lays down mechanics of a financial inclusive bank account. There are provisions for microcredit and a whole suite of products for the poor, and interest can be paid and charged.

So what does this mean in terms of the agent network? How many stores and outlets could potentially be utilised?

I could not give a figure for this but certainly big banks are looking to have combined agent networks of over 100,000 locations. This is required to cater to the needs of a population of 250 million. Although Indonesia has banking infrastructure in terms of ATMs/POS this does not reach the areas where it is needed. Also it is based on bank accounts rather than E-money, so as to work with existing systems. Now additional over-the-counter (OTC) services at banks and ATM services could also be available. Certainly the potential is huge!

But where does it leave the telcos?

Telcos are an important part of this but they cannot participate directly in government payment schemes, which are only to be managed by banks and post offices.

In that case would the same problem faced in India not be encountered? In remote areas typically there are airtime top-up networks that banks find hard to control, as compared to telcos

They do, but banks are now learning to manage agent networks. In any case telcos don’t necessarily control their own networks. In Indonesia top-up is now managed electronically and not by scratch cards. This is complex and margins are smaller, but the potential is there.

Are there any further plans for regulations over 2015?

Bank Indonesia (BI) and OJK now want to harmonise regulations. It can tend to be confusing with two similar schemes when there are differences. This will take time some time to be achieved.

By far the biggest activity will be the launch of branchless banking and G2P payments (government-to-person). The most important so far is the recently launched KKS (Family prosperity card).

In Indonesia since the new president came into power, one of his big challenges has been to more effectively manage subsidies. The fuel subsidy previously took up almost 20% of the national budget, and this does not benefit the poor. Consequently there is a focus on reallocating funds to cash transfers to the poor.

The database that TNP2K maintains has data for over 15.4 million households. Today the majority of these are paid through OTC. As of the end of 2014, 1 million are paid electronically. This is paid in E-money from Bank Mandiri using the Post Office as an agent and through SIM cards of the three largest telcos. This now delivers funds smoothly and is really a huge achievement. In less than 2 months Bank Mandiri created so many accounts; mobile operators manufactured and distributed so many SIM cards.

What is the total volume of G2P?

Well, I can’t share a total amount, but it is on an average 200,000 rupiah per family per month. This year payments will be significantly more, with the offset gained by the reduction of petrol subsidy.

How does the model work operationally with SIMs?

It has been really useful to test this out 1800 households. We firstly found one major problem – when surveyed, every family of beneficiaries had a mobile phone. However, often the lady of the house did not have one. In order to ensure control of the subsidy goes to mothers, we gave them SIM cards.

However, to achieve this we ran into two further obstacles. Firstly, obtaining a photo id for them and registering new SIM cards proved to be a major logistics effort. Secondly, the SIM expires very soon in Indonesia. If you don’t talk or add credit, the SIM could expire in as little as a week. With a top-up of 5$-10$ it lasts but then people put in just cents and that expires in days. That is a major problem for distribution of money. When it’s time for the second payment, the SIM may have expired already.

With this learning from the 1800 household pilot, all the telcos co-operated and gave SIMs with a 5 year expiry period. Although top-up would continue to expire, the SIM card won’t.

Could you please share a bit about the business model?

Bank Mandiri is the contracting agency. They use the Post Office as their agent, for which they give them a fee. The whole business model is yet to be finalized.

Telcos earn through SMS charges to Bank Mandiri, but again this needs further refinement for a sustainable long term business model.

How many have formal identity in Indonesia?

It is difficult to get this information. We find that a majority have Id - Over 90-95% had formal id in our studies. The problems are more that this may have expired when they moved house and have not updated the Id. This is not a big obstacle. Indonesia does have a national ID project, but it is still underway and the supporting infrastructure for reading and using the cards isn’t fully in place.

What distinctive changes do you see in developments in Indonesia as compared to the rest of world?

Firstly there is a strong banking sector as compared to Sub-Saharan Africa. So the Telco model is not appropriate. With 50% urban population there is strong role for banks in urban areas and it’s not just a rural problem. We will see more channel infrastructure develop, with POS, ATM and mobile phones.

When I first arrived here we felt that the appropriate regulations were around the corner. However this took time to improve but the industry learnt and readied itself while waiting, so now providers are ready to roll out the services quickly. The E-money program proved that when the country wants to do something quickly they can. So this is an interesting place to watch.

Yes, we saw a similar pattern with Prime Minister Modi in India. How about retail payments?

Yes, there is a lot of activity planned in this area. The first step is to encourage more consumer payments through formal instruments. There will be a wider use of the debit card as BI rolls out a national non-cash initiative.

Banks that issue debit cards are committed to working together. There are a phenomenal number of POS terminals, yet they are not used as the market is highly fragmented. In one case we noted a record number of 12 POS in one place – this was at the airport so not really representative, but it’s not unusual to see 4 POS at a single location. There is far too much use of cash, and this is now set to reduce.

Thanks so much Michael, this is an incredibly interesting time in the development of Digital Money in Indonesia. I wish you all the best for your projects in 2015 and beyond!

|

Michael Joyce is Mobile Money Policy Advisor at TNP2K where he supports the Vice President’s National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction with advice on policy and implementation of mobile money initiatives to assist in poverty reduction and alleviation across Indonesia. Michael has a background of working within mobile money and financial inclusion for over six years, previously at WING in Cambodia and with ShoreBank International at Bangladesh. |

Charmaine Oak is Author of The Digital Money Game, co-author Virtual Currencies – From Secrecy to Safety

Contact Shift Thought for details of our recently published unique “Digital Money in Indonesia 2014” Viewport.