Blog 7

Dr. Neeraj Oak continues his examination of why Bitcoin is designed the way it is. In this post, he looks at how miners are compensated for their work, and the implications this has on how Bitcoin operates. He concludes with a look at whether a transaction-fee or Bitcoin mining business model is a better bet for the future.

So who are the ‘miners’ and why do they expend computer time (and hence money) on keeping Bitcoin ticking?

Miners benefit the Bitcoin community by using CPU resources to process transactions, so the designers thought they should receive some recompense for their services. In a traditional financial-institution (FI) based payments service, the FI provides the transaction validation service in return for a transaction fee. But it is exactly these kinds of fees that the users of Bitcoin feel are unjustified, or at least far too high. So miners need to be given some other form of incentive to continue providing a validation service and to invest in expanding their service as more users adopt Bitcoin. Miners could also use a transaction fee based system, but this would be unpopular initially and might stop people from adopting the currency. So Bitcoin developed an innovative new solution- to ‘discover’ more Bitcoins.

The term mining is meant to draw a parallel between the process of validating transactions and the creation of wealth through costly labour. When a block is successfully processed, the person who found the solution receives a reward in Bitcoins. This both provides a cash incentive for the miner, but also ties them ever closer to the Bitcoin community, as the continuing success of Bitcoin is the only guarantee of the value of the reward. As such, no miner can ever afford for Bitcoin to collapse, as the value of their earnings from mining would collapse with it. This forces them to either immediately cash their earnings into some other currency or reinvest a portion in expanding their computing capacity to continue to mine successfully in future.

There’s a problem with mining though- inflation. Let’s take an example from history. When the Spanish discovered the huge gold and silver deposits of South America in the 16th century, they were quick to extract as much as possible, mint it into coins and ship in home to Spain. But once that money arrived and started being spent, the Spanish suddenly found that everything started to go up in price. Why did that happen? Well, the total amount of goods and services in Spain hadn’t gone up much, whereas there was suddenly a whole lot of extra money in the economy. What happens in this situation is that people simply outbid each other for the goods they need or want, and this slowly but surely pushes prices up. The result was that went from one of the richest and largest empires in history to an economic basket-case by the 18th century, as the influx of American gold ate away at the domestic Spanish economy.

So inflation can be a bad thing. How did the designers of Bitcoin get around this problem?

The first step was to establish a rule that makes the difficulty of solving blocks become progressively harder after a certain number of blocks are solved. The second step was to limit the total number of new bitcoins that can ever be mined.

Raising difficulty forces up the cost of mining bitcoins, as problems take more computer time to solve. This reduces the number of people willing to mine purely for the Bitcoin reward as time goes on, as the profit margins from doing so reduces.

Limiting the total number of Bitcoins ensures that there is a hard cap on inflation, and that the currency retains user confidence in the long run as nobody can simply ‘print more money’, as is the case with fiat currencies.

There is a problem with the way these rules interact- as mining grows more difficult, and the number of remaining minable Bitcoins grows smaller, the currency might actually become a deflationary one. Add to this the effect of lost or frozen Bitcoins and the deflationary pressure could be quite substantial. The risks posed by deflation are high, but I will cover this in more detail in a later blog.

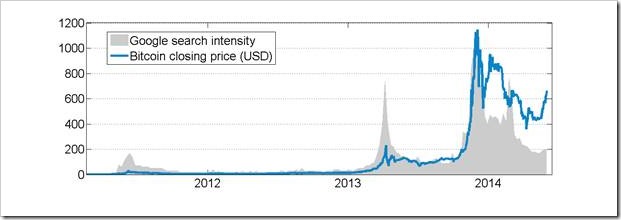

Returning to miners, has the incentive structure offered by Bitcoin’s designers been effective? At the moment, about 13 million out of a maximum of 21 million Bitcoins have been mined. I mentioned earlier that miners are incentivised to keep mining because it helps the Bitcoins they earn to hold their value; unfortunately, while this effect may well be true, it is completely masked by the effects of speculation.

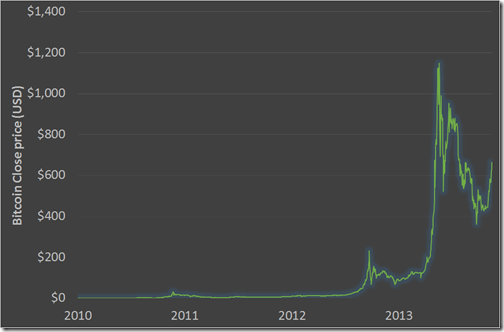

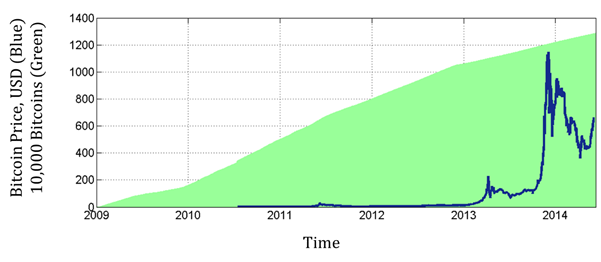

The green shaded area in the graph above shows the total number of Bitcoins in the world over time, and the blue line shows their price. If the main incentive for miners was to stabilise the price of Bitcoin, then there should be at least some correlation between the two datasets. But there doesn’t seem to be any. My view is that this is almost entirely down to the effect of speculators. And so far, it seems to be working in the miners’ favour.

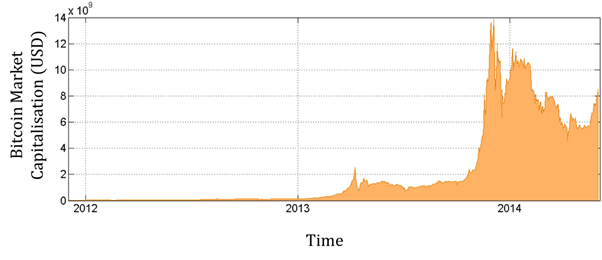

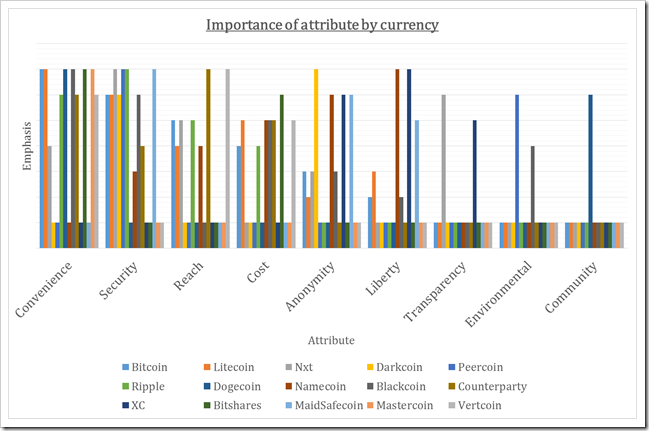

Let’s look at the true worth of all those Bitcoins: their market capitalisation.

The market capitalisation of Bitcoin, shown as the orange shaded area above, is calculated by multiplying the number of available bitcoins by the price of bitcoins at any given moment.

For a commodity that is completely free of speculation and does not get destroyed by usage but is produced at a steady rate, the price of the commodity should slowly decline. At the same time, more of the commodity is always available, and each new unit should grant at least some profit for the producer, otherwise it would not be worth creating. As such, the market capitalisation should slowly increase until it is no longer worth creating more of the commodity, or it is not possible to create any more. This is a rather sober and rational market in which to operate, and it is my belief that this is the business model that the creators of Bitcoin would have envisaged for miners.

Instead, miners face a far less stable business model in which the value of the coins they create rises and plunges wildly. In a sense, they must become speculators themselves in order to get the most value from their mined Bitcoins. Yet by participating in the speculation, they make it even worse, perpetuating what might become a destructive cycle.

My final point on the way Bitcoin mining is designed is to emphasise that mining should be thought of as a stopgap, not an integral part of Bitcoin. It is a mechanism by which the first adopters of the cryptocurrency could operate effectively and earn enough money to keep investing in the growth of the Bitcoin concept. Transaction fees are the real long-term mechanism for revenues, and this is where mainstream organisations should look to invest, not in mining.

I’ll leave you with an analogy that illustrates this point. Bitcoin mining is, in many ways, like the California gold rush of the late 1840s. It’s a chance for people to get rich quick, but it’s also tough, risky and best suited to people with nothing to lose. Big companies did not invest in the gold rush of the 1840s, but they did put their money into developing California by building railroads and cities. In total, the California gold rush dug up around $20-30 billion in today’s money. Compare this to the GDP of California- around $1.8 trillion. That’s around a thousand times more than the value of the gold rush each year. Perhaps investors in Bitcoin should start to look at the more boring but predictable transaction model rather than the lottery that is Bitcoin mining. Because if the gold rush analogy holds, that’s where the real money is.

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0024_thumb1.png)

![clip_image004[4] clip_image004[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0044_thumb1.png)

![clip_image008[4] clip_image008[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0084_thumb2.png)