This blog is part of our series on the development of branchless banking in emerging countries in Asia Pacific. Charmaine Oak (CO) caught up with Thilaksha Kudithuwakku (TK), Mobile Banking Specialist, to discuss his vision on how mobile banking could be adopted by the masses in Sri Lanka, from his experience in carrying out research in such services and segments in the market since 2003.

The Context

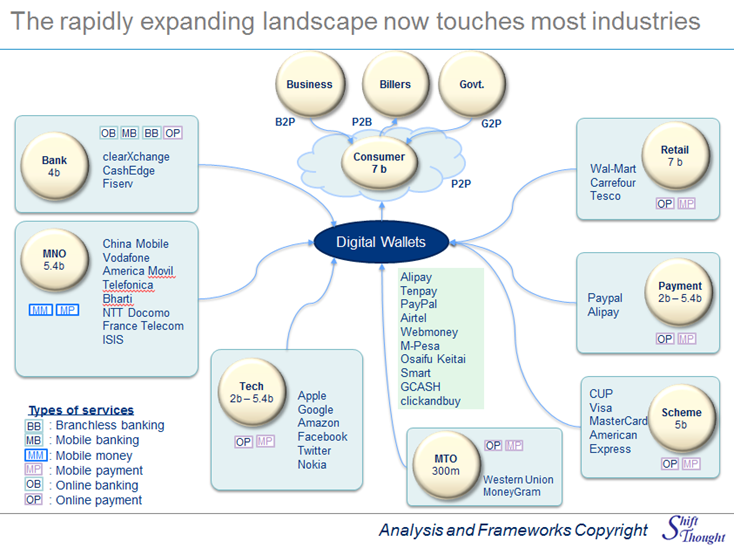

Since 2008 the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has keenly researched the possibilities to determine the most appropriate regulations that could open the door to better financial services through the use of mobile phones. This culminated in the issue of mobile payments guidelines in 2011, for both bank-led and custodian account based mobile payments services. We met up with Thilaksha to understand the progress made so far and get a view on future outlook.

CO: Thilaksha, what originally got you interested in mobile payments?

CO: Thilaksha, what originally got you interested in mobile payments?

TK: I first got interested when I saw the use of calling cards in 2003. Since then I have been keenly interested in putting together that unique combination of factors that I believe are essential for adoption in this unique country of ours.

My first opportunity to launch a service came when I was working at Seylan bank and we launched eCash as an early 1-to-many service back in 2008. Since then I have had an opportunity to discuss the potential with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka who have been most interested in creating a supportive regulatory framework.

CO. What are these very unique characteristics of Sri Lanka that must be considered in order to create the perfect mobile banking service?

TK: Sri Lanka differs from Kenya and the Philippines in that the potential comes from a large under banked rather than unbanked population. People do have bank accounts and are in fact very savvy about managing their money. For instance, they would certainly care if their money is not earning them interest.

What they need is more convenience. Also farmers require a “package of services” that includes for instance the ability to determine the prices of seeds and fertilisers, so as that make the offer irresistible.

The youth are the segment that are most likely to adopt first, and then persuade their elders to have a go. They already use their mobile phones to top-up their friends phones.

Another key segment consists of receivers of remittances from the over 1.7 million migrant workers abroad. The SME segment is another one that could strongly benefit from these services.

A unique characteristic of Sri Lanka compared to other emerging countries is that we still have only 14% of our population in urban areas – so we must go to the villages with our services. Only 12% currently use Internet (though this is growing fast), hence the importance of mobile phones.

CO. Are there challenges in establishing identity and AML/KYC?

TK: The great thing is there is a high level of education and children have already got ID cards prior to taking the GCE O-Level examination. Over 98% of the population have ID cards, and there are also credit bureaus in use.

There is really a relatively very low problem of AML/KYC as compared to other emerging countries.

Since 2011 the Central bank has already issued 3 types of guidelines, basic, standard and extended banking through agents. Unfortunately no bank has yet done full justice to the agent banking model.

CO: What do you consider to be some of the key requirements to be met by an “ideal” service that can quickly gain adoption in Sri Lanka?

TK: I am deeply convinced that we need to think differently to succeed in using the mobile channel in a truly transformational manner. It is a matter of choosing the right combination of technology, marketing messages, channels, visibility and testability to properly make this happen. We need to go to the village societies (samithis) and communicate through “slice of life”, examples and the use of dramas and highly appropriate media.

I also believe that banks have a better opportunity to deliver the best service to customers, but before this can happen they will need to let go of many of the old ways of thinking that are no longer appropriate for taking the new services to the masses.

Each of the target segments has unique requirements based on their lifestyle, access to specific mobile device and service requirements. It is very important to have a multi-channel approach as opposed to a single channel, and to match channel strategy to needs of the market segments.

CO: How has the market responded to the launch of eZCash?

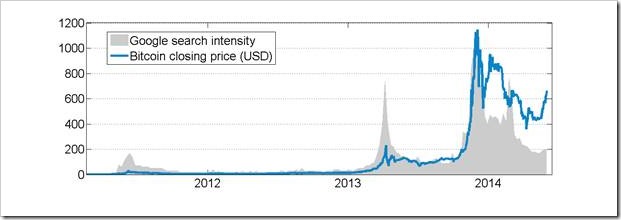

TK: The eZCash service that launched in mid-2012 did obtain a good sign-up of around a million subscribers. However the issue faced is of how to get people to regularly use the service.

At present there is not yet a way to directly transfer money between the wallet and bank accounts – once that is in place it could certainly help.

CO: What are some of the biggest challenges you see that can hinder adoption?

TK: I believe it is very important that the services are not just designed by system providers but rather carefully brought out as a complete solution to address precise needs of our unique marketplace.

It is important to guarantee interoperability of access across all mobile operators, as there are 5 main mobile operators servicing the market.

Customer education is crucial. Unless people know what is available and feel comfortable in using the service it will be hard to raise the level of active users.

Use of appropriate technology is very important. For example, while mobile apps may be the future, what works immediately is USSD. People even find menus difficult to locate and access.

Another big factor is the establishment of the agent network and creating a commensurate business model and commission structure.

CO: Could you please offer some advice to companies seeking to launch services in the Sri Lanka market?

Firstly, An important element is vendor selection, in terms of the platform and their business model. Most of the mobile banking systems currently available around the world have been designed specifically to support the markets of unbanked and banked.

I strongly recommend having a vendor who can carry out the customization required to their existing systems as Sri Lanka needs a unique solution. Market conditions are not as the same as in the countries which have low bank density and high percentage of unbanked population. The banks may look at ways of converting their vendor into a strategic business partner rather than using them just as platform providers.

Secondly, it is crucial to have Senior Management Involvement. Without this it is very difficult for mobile banking services to succeed. Senior Management needs to understand the importance of launching mobile banking in terms of its unique capabilities for providing convenience, outreach of basic banking services and more importantly the capabilities of making payments remotely. Access to payment facilities is a major enabler as once the customer has the capability to easily pay and receive money to and from anyone, the range of financial possibilities expands.

CO: How do you suggest an existing bank structure itself for mobile banking?

I think it is very important to have a dedicated unit with specialized staff members to handle this.

In the current Banking context, although Mobile Banking has become the fifth channel to provide Banking services, it is very difficult to achieve mass adoption without the appropriate model and the marketing/ advertising approach which requires specialized skills and knowledge.

I recently read a report from CGAP that 172 branchless banking implementations have launched around the world since 2007, but CGAP estimates that less than 20 of those have reached 200,000 active users. I believe a root cause for this is that most of the players have launched their services without properly matching the requirements and attributes of the relevant market to their choice of technology platforms and marketing strategy.

Many banks which carry out mobile banking operations in the region already have identified the issue and have established separate units to handle the operation with specialized staff. I strongly believe that it is time for Sri Lankan Banks also to think of having a separate unit under e-Banking to handle the operations of m-Banking. Banks might see this as a costly operation, but it’s not. I see this as a strategic investment as in the future most of the business transactions and payments will be done via mobile communication channels (Mobile Phones,Tablet Computers, Smart watches, Smart TV and new gadgets to come) and therefore banks should be able to go with the trends as they arise, by having appropriate products and processes in place, so as to gain the competitive advantage which could be achieved via the specialized staff.

This will help the bank achieve mass adoption for m-banking while cutting down the advertising costs and more importantly it will create paths to offer innovative mass banking products based on the mobile phone and internet, including Face Book and other social media sites.

CO: What role do you see for the government of Sri Lanka, in facilitating the spread of mobile banking?

The government can play a major role in creating a positive environment for mobile banking and all the related products and services. I strongly believe the government should introduce mobile banking to their projects such as pension scheme, Samurdhi program and Divineguma program. These are programs introduced to uplift the lifestyle of the poor people of the country. The government should encourage the use of mobile financial services in Microfinance projects, train and bus ticketing, tax payment schemes and more, in order to build trust among all segments of society and thus increase usage.

CO: Thilaksha, what are your thoughts and hopes for the future outlook of mobile financial services in Sri Lanka?

TK: I believe there is a huge potential here, as compared to other countries, but only through taking the right approach. As mentioned earlier, the entire marketing and advertising of the service must be precisely targeted to reach the message to the masses. I myself continue to be passionately interested in working to make this happen!

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0024_thumb1.png)

![clip_image004[4] clip_image004[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0044_thumb1.png)

![clip_image008[4] clip_image008[4]](http://digitalmoney.shiftthought.com/files/2014/06/clip_image0084_thumb2.png)